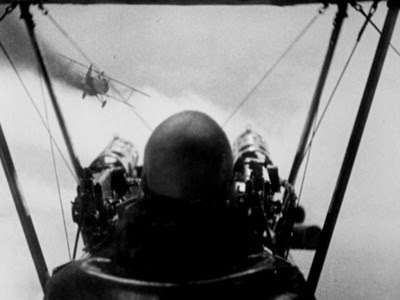

If you want to deep into the real ambiguity of war, the heart of darkness, look no further than the pre-code 1930s WWI flying ace movies written by John Monk Saunders. With dogfights and aerial maneuvers performed with rickety biplanes, sometimes shot at through rear projection and destroyed in stock footage explosions, there's a nice metatextual collage effect at work, adding to a sense of existential aloneness 'up there' in the deadly skies, contrasting with the human-on-human interaction of the barracks. It makes the combat colder, more abstract, like real war can never be properly depicted and so unspools with Kabuki modern anonymity (everyone wears the same evil-looking goggles, making it hard to tell whom from whom unless the actor playing the pilot--and no one else--has a strong, manly jaw. Before the Hitler, Joseph Breen, and Hirohito necessitated a cinematic puscht of anti-war sentiment, the conscience-stricken flying ace films of Saunders were topical stuff, reflecting the forgotten man's deep disillusionment. Looking back from our 21st century high, Saunders' films still loom high overhead as a dark, compelling chronicle of the roots of modernist disillusion and the industrial destruction of man.

An aviator and trainer of WWI fighter pilots during the war, John Monk Saunders was a good-looking, intelligent, heavy-drinking depressive. After the war his stories of WWI aces he knew and trained provided perfect short story and Hollywood script material. He became a hot commodity in Hollywood and married Fay Wray! The beauty that killed the beast! Was he flying the bi-plane that got Kong? Was it Saunders killed the beast? No, but work like his powerful, alcoholic thousand yard stare modernist anti-war existentialism may have slowed our participation in WWII.

As I've written before, I take a strong stance on the importance of death and drugs / alcohol abuse in being able to screen the existential horror of the void and, more importantly, live to tell the tale, and be poetic enough to make it count. Death opens the door to the screaming Lovecraftian horror of the void; the booze allows you to stare right into its gleaming, rotten yellow eye, and gives you the courage to wink back, even as the sheer benumbing horror of it all sinks even deeper into your soul than it would ever sink into the souls of the merely dead. Without booze this grim bargain, which all sensitive poet hunters and fisherman must make every time they watch the light fade from their prey's terrified eye, would be unendurable. Where would Hemingway, Fitzgerald, John Huston, Tennessee Williams, or John Monk Saunders be without the booze to help them see the horror? And without them, would not our generation, too, be lost, falling in a downward spiral like King and Major Kong? You may argue that it is in such a spiral, and you'd be right, but man do we know how to plummet!

Saunders' first filmed story was WINGS (above) in 1927. It was perhaps a turning point in aerial combat war realism onscreen, and underneath it all he provided a probably accurate recording of the bloody birth of the modern man and the nerves of steel that allow him to soar into machine gun fire astride a hunk of balsa wood at 3,000 feet. Audiences loved the aerial stunt photography, and thanks to Saunders they also caught a whiff of the full-on madness of trying to land a flaming coffin into a soft cloud of cartoon champagne bubbles and vampiric courtesans.

But it is later, in the sound era, with series of four magnificent pictures that work almost like an unofficial WWI quadrilogy, where Saunders finds his true lysergic thousand yard naked lunch how to keep your cool even when the walls are trying to eat you calling. The early 30s pre-code era was itself naturally existential. Remember my Forgotten Man? He hurled his lunch across the land, and how a totally ineffectual censorship board made it possible, if only for four years, to get away with actually telling and showing the truth about his widespread poverty, horror, disillusionment, sexual double standards, war-related post-traumatic stress before there was such a word, and the seething resentment over prohibition that the forgotten man was faced with. And Saunders was the right man for the job, giving us a little aerial action in the process via: THE DAWN PATROL (1930), THE LAST FLIGHT (1931), and THE EAGLE AND THE HAWK (1933) and ACE OF ACES (1933). Let's examine!

THE DAWN PATROL (1930)

THE DAWN PATROL (1930)Directed by Howard Hawks (Warner Bros.)

Starring: Richard Barthelmess, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., and Neil Hamilton

Neil Hamilton (Commissioner Gordon from the 1960s Batman TV show) rants on and on about the cold idiocy up the chain of command in this early Hawks sound film, but from then on it gets better. A tale of the men of the dawn patrol, it was remade by Edmund Goulding in 1938 as a vehicle for Errol Flynn and David Niven. Basil Rathbone took Hamilton's role in that one, and his pointed fey affect made thee idiocy rants as great as they deserived at last. As with great Hawks films, there's a querencia, an enclosed shelter within which our brave group waits, drinks, and smokes, sings, and passes out. And like all the best Hawks, we're made aware of every drink poured and cigarette lit, and no one leaves a drink behind half-full. As inHawks' other early sound films like SCARFACE, there are abundant deep, spidery shadows that both isolate and insulate a group of men in a multifunction building, like the HQ/bar/bungalow system in ONLY ANGELS HAVE WINGS. We come to know the layout of the place very well, like a second home. The bunks are upstairs, the bar is downstairs, and the CO's office opens out onto the bar, making it easy to hear your orders, get drunk, and then carry the lightweights up to bed all without going outside in the rain.

I was a big fan of the Errol Flynn remake (which I deemed a piece of great acid cinema here) but that film borrowed, it turns out, heavily from the combat scenes in Hawks' original, and as such should take a knee and heed the older film's wisdom. Richard Barthelmess as Capt. Courtney isn't quite as dashing as Flynn, but he's more believable, more method; when he gets out of his plane after a mission his legs wobble, like mine used to after mowing the grass. His Courtney doesn't come off as dashing, just a guy who survived, and provided what was required, even in the face of daily death. He's far less boisterous than Flynn, and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. is less jolly but more authentically inside a war than David Niven. Sometimes it may be hard to understand why Barthelmess was considered such a star, he's so stocky and low key, peering under hooded, wounded eyes, but there's a lot of acting going on in them while the rest of Barthelmess remains almost motionless, such as the flickering warm light when he sees Scotty come back alive (with bottles). All in all and remake aside, Hawks' 1930 version is the CITIZEN KANE of WWI ace pics, and balances the anti-war sentiment with a more stoic existential acceptance of duty, which is where it comes in as a great acid film, since part of tripping involves keeping your cool and shrugging it off even when the walls are melting and the handrails down the stairs are like two pincers and the steps the tongue of some throbbing scarab beetle, and everyone you see seems to be bleeding even when they're not and you can see the blood pulsing through their translucent skin. Oh my god, so much blood. Maybe it's not the same as 'really' being in a war, but then again, maybe only schizophrenics, war vets, and survivors of 12 hour-long nightmare STP trips truly understand one another. BANG!

After the credits, sometime, the war ends and the surviving pilots go in various directions, usually after some opening scenes borrowed from WINGS and DAWN PATROL of aerialdogfights and crashes or rough landings. Some pilots go home to usher in the early days of commercial flight, in AIR HOSTESS (1933) and CEILING ZERO (1936). Some others go deep into barnstorming and either way, unless they're too shot up or broken, the pilots coming back from WWI always seem to find work, even if it means flying a safe boring air route for passengers, which according to one ex-barnstormer is "like being a trolley conductor." There's also flying for air mail routes in South America, over the Andes ala NIGHT FLIGHT (1933, my appreciation here) or ONLY ANGELS HAVE WINGS (1939).

But in THE LAST FLIGHT (1931)

Director: Williem Dieterle (for Warners)

Starring: Richard Barthelmess, Helen Chandler, David Manners

Cary (Barthlemess) and Shep (David Manners) are too shattered from a 600 foot death spiral to fly anymore. They're discharged from the hospital after the war but don't go home, preferring to bum around Paris and pick up a strange girl played by Helen Chandler from DRACULA (1931). They are, as their doctor describes them, "heading out to face life, when all their whole training was in preparation for death." It was the preparation for death that was, of course, Saunder's job in the war. "I'm afraid they they're like projectiles, shaped for war... hurled at the enemy, they described a beautiful high-arching trajectory, and now they've fallen back to earth... spent... cooled off... useless." He notes that they fell 600 feet and though they survived, it was "like dropping a fine Swiss watch on the pavement - it shattered both of them."

After opening on a wordless montage of war footage that stretches from random explosions and WWI shots of tanks, exploding boats, the overhead bomb money shot from DAWN PATROL, and aerial footage from WINGS, there is, spliced in, anonymous goggled close-ups showing the dogfight that has allowed Shep and Cary to be crippled ex-pats awash in a sea of boozy screwball gibber-gabber. Again it's as if war and strife actually knocks linear narrative out of joint, forcing the actors into ghostly sandwiches of rear projection carnage. It's like stock footage has some gravitational drag, such as the bullfight that will later lure the big Texan to his doom, in pursuit of being "a big success."

Saunders had clearly been reading Hemingway and Fitzgerald before writing this, and it could have become a cult classic if directed by Hawks, or a good dialogue director like George Cukor or someone with a dark-streaked screwball humanism like Leo McCarey, or even Norman Z. McLeod. But in the hands of impoverished German immigrant Willam Dieterle the champagne bubble dialogue sinks to the leaden floor. Maybe Dieterle grew up way too poor to have much understanding of boozy tuxedo modernism or the flow of natural, intelligent English, or was secretly trying to open a second front. He has the actors still over-enunciating like it's 1929 and the dawn of sound, waiting for the other to finish talking, allowing a long pause between each speaker, like a tableful of drunks never would in real life. The result feels like a 1929 Paramount Marx Brothers movie directed by a drunken Todd Browning, with the cast of DRACULA all playing Groucho at the same time with the projector running at half speed. Which sounds great, by the way, and almost is.

An unsolvable problem with THE LAST FLIGHT is that, aside from Barthelmess and Manners, the crew of fellow drunk aviators aren't very hip. It's really only Richard Barthelmess and David Manners that Nikki likes, and we like. The others are all fairly unbearable, especially the creepy masher they can never get rid of (Walter Byron), and the loud Texan played by Johnny Mack Brown, who tackles horses in the street to prove he's still got the old college football elan, and rocks the stagiest of Texas accents. Luckily for us Mr. Manners, despite his affectless line readings, comes off especially well in his scenes with Chandler, much better than he did in DRACULA, where he was always trying to boss her around: "We're going to think of something cheerful - aren't we?" You just wanted to slap him and open the window. But as a tippling pal, Manners' dreamypoeticism finds a great natural outlet and when he dies at the end in a taxi cab and claims that "in a way this is the best thing that ever happened to me" I believed him. And it's understandable that both he and Helen Chandler would be so drawn, feel so protected by, the quiet strength of Barthelmess' scarred pilot, he's rooted, planted, and they seem to float when standing still, their eyes following wisps around the room only the two of them can see, almost a feypre-war version of Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake.

And the similarities of DRACULA and FLIGHT don't end there: Chandler's character Nikki is much more like the Mina in Stoker's novel of DRACULA than her Mina was in Todd Browning's adaptation. In the novel she becomes a kind of revered icon-mascot for Van Helsing, Harker, Dr. Seward and Lucy's three grief-stricken suitors, including the Texan. If Walter Byron's sleazy masher was Dracula, it would all be set, but in a way, the war already is, making it really like Dracula part 2, wherein Manners, Chandler, Van Barthelmess and co. all try to drink away the awful memories of and wounds from battling the ranks of the undead. In real life Chandler would experience kinship with monsters horrified by their lack of recognizable mirror reflection, and boozing, as Wiki notes that "she ironically fell victim to alcoholism later in life and was badly disfigured in a fire caused by falling asleep while smoking." And of course vampirism is a great metaphor for addiction, alcohol, morphine, or the horrors of war. Addiction and war are actually the keys for understanding true existential terror, the two keys which opens the lock of greatness in art and literature. In addition to DRACULA it makes a great imagined sequel to THE DAWN PATROL, and a perfect distillation of how Saunders imagined the post-war Paris blues, of trying to escape one's broken watch status via the icy abstraction of martinis and a beautiful, hard-drinking girl.

Throughout the film the idea of being 'a big success' is played with, and the competion to be the last one in the room with Nikki is part of that, and also what drives Francis to ultimately kill Walter Byron's rapist-masher journalist, requiring Francis' subsequent disappearance into the Lisbon shadows. "This is the first time he's looked truly happy," notes Nikki. Manners has been shot in the fracas, and a sense of VERTIGO / Purloined letter circular death drive-aliciousness ensues. As he slowly dies in the back of a cab, Shep reports feeling like he's falling, and falling like he and Cary did in the opening scene over the skies and screens of France. "He was ready to die once, and he was ready to die again," laments Cary. Here it is, the love affair between Barthelmess and Manners, the way men bond eternally in the field of combat, like orphans forever clinging to rafts during battles with shadowy Robert Mitchums. "Camaradeship was all we had left." And maybe that's what the real lure of war is for men at home: as an escapist grim fantasia, a place where it's just buds against the world, fire arms instead of nagging wives, the chance to prove one's mettle when it's all stripped down to just you and the guys experiencing the same hell the next seat over. And Barthelmess feels right at home nesting on the cheek of a dying Manners, his face contorting into a slow burn wide-eyed terror at being finally unable to save his gunner's life. But when it comes to pitching confessional woo to Nikki in their private train car back to Paris he seems to doing some vile burlesque of what a lipless man would think having lips is like.

Then, in 1933 Saunders wrote two movies that reflected a new, distinctly anti-war to the point almost of isolationist propaganda stance. This was just when the need to get involved in WW2 was vastly more important than most people in their bitter depression disillusionment then realized, because as Mick La Salle notes in his chapter on Barthelmess in Dangerous Men, "In the same year (1933) that The Eagle and the Hawk and Ace of Aces debuted, Adolph Hitler came to power in Germany. Had the United States and its allies found the will that year to throw a net over Hitler, tens of millions of lives might have been spared." Well, anyway, they're great stuff now that they can't do any real damage to freedom.

THE EAGLE AND THE HAWK (1933)

THE EAGLE AND THE HAWK (1933)Directed by Stuart Walker (for Paramount)

Starring: Frederic March, Cary Grant, Carole Lombard, Jackie Oakie

The video art at left makes the film seem like some love triangle between Frederic "King of the Triangles" March, a still rising Paramount star Cary Grant (in the same year he played opposite Mae West in her two best pictures), and a vamped-to-the-point-she's-ceased-to-look-human Carole Lombard (billed only as 'the beautiful lady' she seems daemonic enough to be a bit like the bloofer lady in DRACULA). But Cary Grant and Lombard never meet in the film. Note in the art at left Lombard more resembles a wife or WAC in a WWII home front propaganda piece rather than a mysterious sympathetic ear wrapped in ermine. And Cary Grant has a righteous smolder as if about to do something truly heroic, instead of being the sociopathic if ultimately loyal gunner who acts as a shadow figure to the conscience-stricken pilot played by March, who has to get progressively drunker to keep it together, to the point a grinning French general pinning a medal on him can smell the alcohol on his breath even in the pouring rain! Death, where is thy sting?

The thingthat tears the game up more than anything for Jerry is that he can't admit how much he loves to kill. When he comes back from his first foray over the lines he's exhilarated and giddy only to find his gunner is dead behind him. From then on, he's horrified not by fear of being killed, but of being responsible somehow for the deaths of his gunners (he loses five in a matter of months) while he gets his kicks. These bi-planes have never before seemed so rickety, ready to fall to pieces at a moment's notice. When one of his gunners later simply falls out during a loop-de-loop maneuver, March's decent into alcoholism and existential guilt goes from spiral to straight downward dive-bomb, but man is it exciting, even if it is, in the end, alone, with only grim reaper Cary Grant to make sure the last stain of shame is erased, in the name of the Observer Corps.

What's less excitingis the way, just like Kirk Douglas in PATHS OF GLORY (1957), March's self-righteous anti-war stance is very convenient as long as its not going to be effective. His hatred of his job depends on making his commanding officer the bad guy as far as doing what needs to be done to win the war. March's performance modulates continually from scene to scene, his veneer never breaking, staying polite while his conscience tears him apart inside, resisting the urge to go off on his preachy horror. Then, during the big binge in his honor after he shoots down Voss, a Richtofen-like ace who's barely out of his teens, March finally snaps, interrupting his fellow flier's drunken singing with a rant of "I earn my medals for killing kids!" He then staggers off to his room and kills himself. La Salle notes that Jerry's suicide has a real-life parallel reflecting March's character as being very close to Saunders' real life booze-enhanced turmoil,"Seven years after the film was made, Saunders, age 42, hanged himself." (105)

|

| Saunders and wife, Fay Wray |

I'd hazard a guess too that, for one of WWI's more peerless Air Corps. fiction authors, Saunders' lack of actual combat experience equal to that of his characters reflects his guilt more than his characters' killing kids. This is perhaps the one weak aspect of his work but as far as weak aspects go, you won't find these kinds of sentiments voiced so clearly anywhere else in pre-code film but with Saunders. Other writers were either anti-war pacifists, or "over there / over there" lemmings but Saunders really explored the actuality of the grisly homicidal fish that bites the propaganda lure, with a boozer's realization that they were two sides of a same lousy nickel-plated excuse to get away with murder.

ACE OF ACES (1933)

Director: J. Walter Rubin (for RKO)

Starring: Richard Dix, Elizabeth Allan, Ralph Bellamy, Theodore Newton, Joe Sauers

It's a complete reversal, the discussion between Rocky (Richard Dix) and his fiancee, Nancy (Elizabeth Allan) of principles, lemings, and the difference between someone whose not a sucker and a coward. While the parade footage unfurls below, Dix sculpts a winged angel in his loft, oblivious to it all until Nancy's righteous salutes drives him into the next scene, walking into the barracks to meet his fellow fliers while a guitarist sings "Ten thousand dollars for the folks back home / ten thousand dollars / for the family," while they roll up the possessions of the downed flier whose bunk Rocky's taking.

It's a startlingly modern scene, as the other pilots have ghoulish hipster freedom that seems way too modern for the 1918, or even 1933: "This is tombstone Terry the Tennessee Terror, otherwise known as Dracula!" notes Rocky's tour guide, introducing one of the fliers. The man leans forward to eye Rocky's neck, "Welcome to the ranks of the undead!" Man, these cats are too cool even for 1933. They act like they would be at home scoring coffee from Walter Paisley or swindling Tony Curtis out of his sax or chasing James Dean around an abandoned swimming pool. Weirder, they all actually have a pet of the power animal emblazoned on their ships: Rocky has a lion cub and there's a chimp who drinks to cope when his owner heads off to battle, a dog, a parrot, and a pig with an iron cross tattoo. Then there's the ingenious way Rocky's artist's understanding of natural light to his advantage in dogfights. He becomes an ace, racking up his black Xs ala SCARFACE, which came out the previous year, and clearly made an impression on Saunders, to the point he borrowed Hawks' machine gunning the calendar over a montage of explosions and bullets. Rocky chokes on the trigger at first and has to get shot before he mans up, but the boys celebrate his kill, badly staged with rear projection as it may be, and he realizes that he may never make the grade as a sculptor, but slaughtering his fellow man in multimedia collage solo performance art earns him great fame. But what is the message of this art? When we see the bloody face of the enlisted man Dix smacks with an ammo belt we know we're not supposed to be buying war bonds in the lobby.

|

| The Lemming and the Lion |

All in all, Rocky ends up being the more complex and interesting figure than March's Jerry in EAGLE. March endures his tenure as ace, but any joy in the sport of it falls instead to Cary Grant's sociopathic gunner. We know from DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE that March could have chilled us to the core as Rocky, but Dix is almost better for being less versatile, more stiff (in both sense of the word). Just as Cary shoots an unarmed parachutist, Rocky shoots an unarmed German cadet who was just dropping a chivalrous note. Naturally this poor cadet also winds up in a hospital, next to a head-shot Rocky, who finally snaps out of his psychotic stupor and rediscovers his humanity. But he was already self-aware, as good artists must be, before the film began, so it's understandable he would relapse when his record is threatened by a kid known as the "Fargo Express."

Luckily there's a happy ending, albeit with a strange 'is this just a dream' quality, like the end of TAXI DRIVER or VERTIGO or LAST FLIGHT. After Dix survives one final foolish assault, he winds up back in the garden in Nancy's arms: "We'll live only for ourselves, and by ourselves," she says, in an eloquent if impossible advocations of the romantic ideal behind isolationist pacifism, that America could take all the time it wanted to lick its wounds and Europe could just sort itself out. Being an American was still in a whirlwind romance with itself, practically a teenager at 157 (that's just 18 in human years), and promised a honeymoon after its violent civil suit nearly cost them a divorce, and the war wiped out so much of its finest men and left the rest of them unemployed, shattered like watches. By 1933 it was clear that the nation would never get a chance to get comfortable with itself before being shipped off to die in some other guy's war. Rocky's last line, though meant as a joke perhaps, leaves a chilling after-effect: As he and Nancy embrace in the garden, Rocky eyes the garden gnome that bugged him in the film's first scene, noting cryptically, "I still don't like the looks of that guy."

The gnome is Hitler.