October evenings in 2016--the usual chill of autumn warming the corpsey cockles of my hideous heart gone cold with heady heat. Has the Earth finally run dry of autumn leaf snap crackle and pop? Here in the East, a C-note of an October day barely resonates before summer muggin' flattens the coffers. In other words, this Halloween needs to get drastic. Luckily there's that first 7 days-free subscription to Shudder, which actually does curate and has pretty good taste --lots of 70s-80s Italian art-horror/giallos. Maybe it's age, but Lucio Fulci's 1981 Quella villa accanto al cimitero aka HOUSE BY THE CEMETERY has sure come along in my esteem. Maybe I'm finally mature enough to admit my prejudices against Italians and confront my childhood fear of a certain basement in our old Lansdale PA house in the 70s. (in particular the crawlspace). If you were ever afraid of the basement yourself, back in the time when each unaccompanied step was a huge endeavor, and when just going down there to get something for your mom while she was making dinner was so scary you'd race back up the stairs at the first tiny creak (even if you knew you made it)--then you owe it to yourself to revisit. Sure, there's a pretty fake bat involved, but we've all seen worse, and at least the wings flap and we wouldn't want Fulci to kill a real bat just for a movie like, say, old Ruggero.

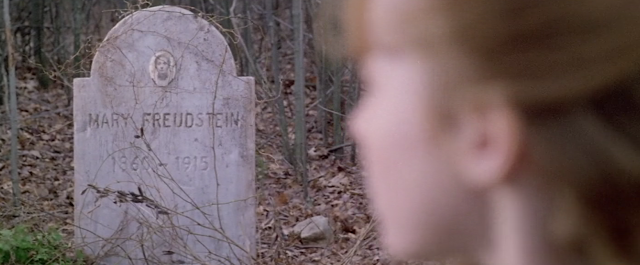

Before diving in, a word of warning--even some of Fulci's fans aren't huge fans of this movie due to its many confusing anti-ellipses and stubborn adherence to paranoid nightmare logic. Me, I like it better than most of his others in his undead series (City of the Living Dead, Zombi 2, The Beyond) as he keeps the focus so narrow--so localized and nightmarish, tapping the same vein of cabin fever time-bending paranoid 'always been the caretaker' interiority that make films like The Innocents, The Haunting, and The Shining (see Pupils in the Bathroom Mirror) so effective. Nothing evaporates the supernatural like the intrusion of cops and shrinks, fire arms, witnesses, panicky groups of holed-up survivors, reporters, etc.-- and nothing condenses it quite like communication failure between isolated, dysfunctional family members. In House it's the Boyle family --the father, Norman, is an academic researcher lugging wife and eight year-old son to New England for a six month stay to 'finish the project Eric (his mentor in grad school) started for the university' played by giallo mainstay Paolo Malco, Norman has a habit of staring conspiratorially at the camera as if its his Mr. Hyde wingman--especially when his emotionally drained and tantrum-prone wife Lucy (Catriona MacColl) is in his arms and can't see his face--meanwhile too people in town say he was up there a few years ago with his daughter--he denies it and doesn't have one, but the Malco stare suggests. Lastly there's Danny Torrance-style psychic son Bob (Giovanni Frezza--burdened by one of the lamest voice characterizations in Italian horror dubbing history). Bob's main communication is with the murdered girl, Mae Freudstein (Silvia Collatina) who urges him not to come--but what parent ever heeded a tow-headed third grader's babbling (and why isn't he in school?). There's also the ever-enigmatic and smoldering-eyed Ania Pieroni (the music student young witch in Inferno) as Anna the babysitter.

No Italian horror film ever just rips from one source, so though the Boyles have a passing resemblance to the Torrances, the presence of Anna evokes passing vapors from Gaslight (all through sultry stares --no words) though never enough of either one to settle and become 'predictable.' Like Argento, Fulci was coming to the horror genre from mysteries / giallo procedurals, where keeping audiences guessing who the killer was meant having everyone be slightly suspicious--everyone is hiding something--or so it seems. People keep mentioning the last time Norman was up there and he says they must be mistaken but he's that shifty-eyed Italian kind of giallo-brand ectomorph--thin enough that he can be mistaken for a woman in a long black raincoat (and vice versa) with eyes that make you suspect he's having an affair with or trying to kill nearly everyone he meets even while his actions and words are all regular scared family man; and the mom is emotionally unbalanced, refusing to take prescribed pills ("I read somewhere those pills can cause hallucinations") and losing shit; then taking them and feeling great; and then being attacked by a bat, and so forth; and there's the beautiful blue-eyed blonde boy with that terrible terrible voice and his dead friend Mae;

but the graves run right under the living room floor. When asked about the grave in the hallway, dad dismisses it, "Lots of these old houses have tombs in them," he says "because the winter's cold here and the ground is too hard for digging." Do those Italians know that shit happens in New York too?

Lurking on the threshold between Lovecraft and calculated absurdity of Bunuel in its deadpan execution, it requires a reckless willingness to let go of reason's handrails and fully embrace the primal anxieties of nightmare logic side-by-side with playfully enigmatic deadpan paranoia, evoking the wry termite wit of Michel Soavi's La Setta and Stagefright but with more genuine dread--the kind of attention to wringing maximum suspense from random things like a steak knife being used to turn a key in a rusty hinge, the camera pulling up close and the suspense rising with the intense chalkboard squeak of dry bold slowly turning while dad comes ever closer to slipping his grip and slashing open his wrist (or having the knife blade snap off and go ricocheting around the kitchen before lodging in someone's head. But then the door opens--Norman flashes the flashlight through the thick cobwebs and we wonder if Freudstein really does live down there or is some kind of a ghost. And then--before Norman can look around--a bat attack. It's quite a sequence - practically real time from when Norman wakes Lucy up (the barbiturates lining up on her night table like little troupers) to the death throes of the bat - a complete wind up all around from waking up refreshed after a night of (presumably) Valium and sex, and winding up back to being the sobbing out-of-her-depth nervous breakdown

TICK-TOCKALITY and MOLASSES LIGHTNING

And then, as the basement keeps opening, the weird mix of nightmare logic and deadpan humor shifts to straight nightmare. No other film of Fulci's is so rife with childhood nightmare faithfulness, and so void of cold logical counterpoint. Italy's other great horror maestro of the period, Dario Argento, still turned to logical cops and psychologists for eventual explanation but in House Fulci forgets about cops and rationale as the time window is just too short. By the time the progressively more deranged and horrified recordings left by Norman's mentor reach the part about Freudstein keeping himself alive in the basement via a steady stream of replacement organs and limbs shorn from new tenants. Bob is already locked in the basement, with Freudstein--one of the most genuinely unnerving Italian walking corpses--shambling towards him. As with Carpenter's Halloween (its sequel was in drive-ins the same year as this) this has sort of melting clock tick-tock momentum, wherein time moves slower than real life while never actually being in slow motion - so moving across a room to open a locked door (ala Leopard Man) can seem to take forever the more you crosscut. For example if we see a Laurie Strode running from point A to B and then cut to Loomis walking down the street from house 1 to house 2, we wouldn't cut back to Lauruie now running past point C or D but still running past B where we left her --then when we cut back to Loomis he'd still be walking from house 2 to 3, back to Laurie running past D. It's an editing strategy that subverts our the narrative pacing expectations originally set up by DW Griffith who invented crosscutting as a narrative style in 1909's A Corner in Wheat to create that nightmare pacing feeling of running through three feet of sucking mud while some being slowly advances towards you. Usually crosscutting liberates us from time's tedious aspects while enhancing our desire for the two separate threads to finally meet (the pursued or endangered heroine and the cavalry riding - riding to her rescue), which flatters our paranoia (we sense our desire will be met at the conclusion of the sequence, due to associative tendency created through signifier expectation: show me an apple near a pointed black hat and I'll think its poisoned with sleeping sickness, show me a racing squad of cop cars crosscut next to an isolated young woman slowly opening her attic door, and I'll think the killer is up there -- etc. Few American auteurs dare screw with this formula the way Fulci (and Soavi had) until Demme with Silence of the Lambs (when it turns out Crawford and company are rushing an empty house and Buffalo Bill answers the door at Mrs. Bimmel's for Clarice, alone except for a standard issue side arm.

A similar rupture even occurs in the time-frame of Cemetery as well, between the two children on opposite sides of the life-death divide, separated by 60 or so years, where time is much more fluid in both directions, which we're not used to. This angle confuses some people in its ambiguity (especially the 'huh?' ending). But if you know Antonioni's BLOW-UP (1967) and the birth of LSD symbolic melt-down post-structuralism and the 70s movement towards ESP, telekinesis, past-life regression, Satanism, post-Manson cults, deprogramming, near death experiences (NDEs), Nigel Kneale's The Stone Tape theory, and the way in which strange visions and dreams might well be some denizen of your house in the far future channeling your ghost (wherein you might be talking to your unborn great granddaughter and not even know it), then yes the ending makes perfect sense. If someone from the past can visit our present why not vice versa, who knows we might be from the future - a visi on they're having in the past from around a seance table.

Whether or not Fulci had seen The Leopard Man (1943) by then--with little Maria's blood coming in under the door as her mama rushes to unlock it--is incidental. He takes that one pivotal moment -- a key scene in nightmare horror no one who's seen it can forget, and drains it of all cultural, feminist Jungian-archetypal symbolism, and mixed emotions (our relish knowing mom deserves to have this death on her conscience)--then distills it down into pure fear, turning the whole second half of the film into one prolonged, torturous child locked on one side, parents frenzied on the other, like a crazy man who distills a gallon of vodka down to a pint of 190 proof Everclear just so he can then take an hour and a half to sip it straight with no chaser. He may be dizzy, nauseous and trembling by the end but by god is he drunk.

My problem with Fulci's other films in his undead category, such as The Beyond (also 1981) is that it's all over the place, spread out into hospitals and cops and corpses with pink Jello-pop acid waves and tarantulas, and seeing eye-dogs and half-headed zombie broads--all fine stuff but the broader the canvas the less effective the horror, to my mind. All the true classics involve structural collapses of the social order, patriarchal symbolic orders toppled by intrusions of the unassimilated real, in HOUSE the cast is kept down to a handful-- there's no cops nosing around, no red herring "pervert" suspects, and the supernatural element is kept on the DL --once people are killed they don't get up and walk again, or wink in and out of existence (as they do in City of the Living Dead), they just get hung up on the basement laundry line for Freudstein's use in his self-Frankenstein home repair.

Thus while many critics will say it doesn't make sense that people take so long to walk say from one room to another and no one does the smart thing like call the cops or leave but in dream logic it makes sense; dream logic isn't an excuse for lazy coherency, to just toss whatever crap together you want and call it dream-like. The structural geography of the dream landscape is just as organized and cohesive--each element corresponds to aspects of a psyche in turmoil, as in the CinemArchetype series, with Freudstein as the Primal father devouring his young like Cronus. Whereas something like, say, American Werewolf in London will rely on dream sequences to justify senseless but visually interesting 'trailer-ready' moments, such as a squad of werewolf Nazis (left over from Song Remains the Same) bursting into the family living room and machine gunning everyone. In doing so Landis betrays a faith in the permanence of conscious perception that pegs him as part of the provincial pop Spielberg-Lucas-Chris Columbus school of wide-eyed wonder. The kind of naivete that insists of gruesome latex transformation scenes, and issues like waking up from your rampage naked (your clothes having been shredded off), the kind of naivete that comes from having not taken mind-altering drugs, experienced drastic social upheaval or had mental illness issues (they're all the same thing, really). Take as opposition to that the more grey-shade psychic breakdowns from more literature-based European immigrants refracting the start of World War 2--the shadow of the wolf over Europe vs. the promise of the New World--in The Wolfman (1941) and the original Cat People (1942 - below). In the latter especially I recently made careful observation of the shadowy transformation scenes and noticed that in the transformation isn't rendered by effects but by black on black animation (if you look closely in the dark shadows in the corner of the pool room you can see an animated black ink splotch), her transformation back is shown from paw prints becoming not bare feet but high heels! The camera doesn't dwell on it, merely pans away, but the implication is truly marvelous in a true Camille Paglia-style fusion of the chthonic feminine and high fashion glamazon.

But Fulci, a dream logic master, doesn't need dreams within the narrative to infuse things with weird imagery; rather the film's entire language is rooted in the figures and narratives of childhood nightmares, just as Wizard of Oz and Alice in Wonderland are, and films that show reality from the point of view of a paranoid schizophrenic, wherein sensory perception merges with hallucination -so that, Dorothy finds everything in two-strip color, the farm hands all halfway between their archetypal dream selves, causing her to kill Mrs. Gulch by drowning her in the water trough, killing any older woman wearing red shoes and stealing them; Alice chasing real white rabbits around the woods, or leaving them to rot outside the ice box. Like The Innocents or The Shining, Cemetery is a study how one becomes the other, in understanding the importance of isolation for reality to bend - the way cops and psychiatry officials dispel it by trade and presence (the only outsiders are dispatched almost as soon as they enter, via axe or poker); a cop's whole training, and the court system, and doctors, is to clear away the cobwebs and separate fact from fiction, the very things that drive people into fits of cabin fever murderousness, the ghosts coming out when there's no one around to dispel them with the lamp of logic.

Therefore too comes the realization that a terrified kid locked in the basement, hammering at the door screaming and pleading while his mom pounds on the other side and the killer lurches slowly across the room--might run on and on, time melting down to stasis, the terror mounting like the swinging of a pendulum, or the slow ascent of a roller coaster. It doesn't matter in the end if the threat is actually real - it can still function along this line - in fact the two might need each other --the isolated paranoid schizophrenic and the supernatural Other like opposite polarities with a genuine demonic manifestation the lightning strike.

"Oh God! His voice... I hear it everywhere!"

Freudstein's disruptive manifestation comes even audio mimesis, a river of Satanic voices and--possibly--his past victims, such as Freudstein's unholy Bluto-style laughs of pleasure when killing the real estate lady or the way he cries in a child's voice (possibly Bob's) when injured, a voice that sometimes doubles itself to sound like a chorus and occasionally interrupts the cry with a tiny laugh. Are these the voices the ghosts of murdered children or is it a by-product of stealing their limbs, (including his own daughter's arm). Is this some kind of ability to mimic his victims to lure new ones down, ala Attack of the Crab Monsters? or does he just cry like a little baby? If you need an answer, then you may want to know for sure whether the hauntings in The Haunting and The Innocents are all in the projections from the deranged mind of a repressed middle-aged virgin hysteric or actual ghosts. Again, Schrodinger's Cat, man. Horror lives in amnesia and the dissolution of the line between hallucinations and reality.

Freudstein's disruptive manifestation comes even audio mimesis, a river of Satanic voices and--possibly--his past victims, such as Freudstein's unholy Bluto-style laughs of pleasure when killing the real estate lady or the way he cries in a child's voice (possibly Bob's) when injured, a voice that sometimes doubles itself to sound like a chorus and occasionally interrupts the cry with a tiny laugh. Are these the voices the ghosts of murdered children or is it a by-product of stealing their limbs, (including his own daughter's arm). Is this some kind of ability to mimic his victims to lure new ones down, ala Attack of the Crab Monsters? or does he just cry like a little baby? If you need an answer, then you may want to know for sure whether the hauntings in The Haunting and The Innocents are all in the projections from the deranged mind of a repressed middle-aged virgin hysteric or actual ghosts. Again, Schrodinger's Cat, man. Horror lives in amnesia and the dissolution of the line between hallucinations and reality. |

| Norman stares directly into the camera a lot - for the same reason most actors never do |

Walter Rezattis score rocks along all the while all, surging between soapy melancholic grand piano and crescendoes of church organ-driven prog rock, taking long pauses here and there so we can hear the pin drop, emphasizing all the weird random noises that come in and out of the mise-en-scene This is a chamber piece movie as big as all outdoors while seldom leaving a few rooms, capturing the weird way time mirrors across itself, the way modern horror comes rupturing out of the ground like oil gushers of the putrid dead in between cliffside romantic clinches so that sweeping concert piano virtuosity --which normally is my least favorite Italian soundtrack instrument--fits elegantly as counterpoint--that great soundtrack style originating with Ennio (as far as I can tell)--where antithesis brings depth in a way the on-the-nose telegraph orchestration of Spielberg types like John Williams and Howard Shore would never imagine--as nowhere is the line between the 'experienced' and the virgin more sharply drawn than in music. Rezatti ain't no Morricone, or even Goblin but he is a kind of Keith Emerson-meets-Bruno Nicolai fusion, and as always with Fulci music is used sparingly, effectively, sometimes jarringly - roaring to life to cut off actors' last word or stepping on their first, with even what sounds like a 'play' button clicking in the mix. I've written too much validating accidental Brechtianism to just presume Fulci 'missed a few spots' in the sound editing, especially with all those earlier marvelous musical flourishes.

I AM LAZARUS, COME FROM THE DEAD

(but as a kid, so who believes me?)

Another example of Fucli's open-ended death/Lazarus metaphors (ala Mike Hammer voom! vavoom!): Bob, the child, racing in terror - the camera running up behind him with the score roaring to life with crazy synth squiggles of twisted menace--he falls atop a grave, the ghost (?) of its occupant's child, Mae Freudstein (redheaded child of horror Silvia Collatina) lifts him off grabbing him by his arm, which stays folded like he's in a coffin; Mae turns out to have been chasing him in a game of tag. But now Bob has to run home for lunch; promises -as we all have--to race back out right after. Mae watches as he runs back towards the house before saying (with a robotic fatalism) "No Bob, don't go inside." but the score surges to life again and cuts off her last syllable.

We saw her in a flashback to her own period (Victorian, judging by the dress), earlier (and again later) saying the same thing, as if in a trance, after we've heard her say it to Bob, while he's in a trance, and sees her talking to him from the window of the old photo of the house they're moving to, so one imaginary friend in the early 1910s is having a conversation with a real boy in "present" time (1981), etc. The girls admonition in the graveyard --"you shouldn't have come, Bob" has a chilling unemotional frankness far beyond either scary emotion or kids trying to act.

It's not like Bob really has a choice; as a kid is never listened to. Even after he sees his babysitter's head bounce down the stairs he's unable to get this across to his disbelieving mother the type of parent who if you came to them covered in bruises would chide you for having such a morbid imagination when crying for attention. Of course from that horror then comes the comedy of the idiot Bob down in the basement alone shouting "Ann! Mommy says your not dead!" when the last time the door just swung shut down there and locked by itself and something killed her. This is just one of the ways Fulci builds terror in a viewer, the raw molasses slow illogic after all that high-toned paranoia reaches back to the fatalistic dread of kids who aren't heeded until it's too late. It's the big fear preyed on in all the best horror films, most recently in Let the Right One in and It Follows, of being a kid in danger and adults around either unwilling or unable to notice or give your fear the slightest heed. Not until the blood runs under the door will they believe you and even then will rather believe it's somehow a result of your own morbid imagination.

NIGHTMARE LOGIC III: Schrödinger's Cat People

Later: The real estate agent's corpse is dragged across the kitchen and down the stairs, leaving a wide streak of blood; the close-up of blood on the wooden floor is suddenly interrupted by a sponge coming into frame. We wonder for a half-sec if Dr. Freudstein is actually cleaning up after himself, but then see the floor's being cleaned by Anna, throwing down a big mop and bucket. But is she cleaning the blood or was the blood gone before she started cleaning or is she in league with Dr. Freudstein or is Lucy just hallucinating and by now shrugging it all off (or is it dead bat blood)? Lucy comes into the room in her robe, "What are you doing?" she asks. Anna gives her an enigmatic look that could mean a) what does it look like, genius? You people leave blood everywhere. and b) I'm going to fuck your husband. But instead: "I made coffee."

Lucy continues, oblivious: "What a shame you didn't come with us to the restaurant last night." This gets a knowing, vaguely contemptuous and cuckolding stare even closer and straight into camera that could be read many ways, as its no doubt meant to. Since a lot of these signifiers all come from mysteries Italian filmmakers are used to conveying the 'everyone's a suspect with the same approximate build, male and female' suspicions. It even continues with the implication Anna is bringing a tray of coffee into Norman at this desk, but instead in the reverse shot after her muffled voice we realize it's Lucy and shortly after all that's forgotten when we see it's Lucy behind the tray - and that whole aspect evaporates. Lucy ccomes out with groceries and we think we see Norman driving by in the car but can't tell - did Lucy drive the car and he stole it leaving her to walk hme with two bags of groceries through the woods, did he say he was going to NYC but really is haning around the library listening to disturbing tapes of his predecessor's rantings (accompanied by POV shots of Freudstein's 'workshop' replete enough gore to repel most anyone no matter how fake most of it looks.)

It would be unfair to make Fulci account for the lack of resolution in all this unspoken

'let's drive the wife insane' red herring implications anymore than in the 'almost affair' between Richard Harris and Monica Vitti In Antononi's Red Desert. There's no trope or cliche that sits still and allows us to situate ourself into what kind of movie this is, which again maddens the either/or types. They can argue that since nothing comes of it, plot-wise, one can argue it's just a waste of time that goes nowhere, Fulci fooling around with the bag of enigmatic stare tricks so beloved of Italian genre filmmakers and French film theorists.

But one can argue to the genius of that - for it generates a sense of paranoia and unease if you submit to it, that helps amp up the shocks to come as they seem further and further afield but in actuality are remarkably blunt and close to home, like tricking us into looking at a car driving from far away and then after our eyes have adjusted, stabbing us in the throat from behind with a scissors. Fulci critics wouldn't dare say Hitchcock wastes our time with the Melanie Daniels'-Mitch Brenner meet-cute romance in The Birds or Marion Crane's embezzlement in Psycho. Well, Fulci does the same thing within the confines of wordless stares! In all three the suspense and fright comes seemingly from left field - we're not given to expect birds or knives or monsters in the basement because the cinematic signs are all lining up for a different movie, one we've doubtless seen: in The Birds, the story of a spoiled city heiress finding love and meaning while hiding out in a small waterfront fishing community (in the vein of Anna Christie, The Purchase Price, He Was her Man) is sideswiped by the bird attacks, so that the birds fly in under our radar in a sense, as in Pyscho where there's no signs of what's coming in the shower as we believe we're seeing some sexy noir thriller where a woman steals from her employer to run away with her handsome lover.

|

| Did Anna Pieroni inspire this iconic NG photo from 1985? |

Earlier, seeing she's stressed out over the move, husband Norman asks if Lucy's taken her pills (we never learn what they are or hear of them again). Though clearly very rattled by the goings-on in the house she says no, she hasn't been taking them because "I've read somewhere that those pills can cause hallucinations...." He looks at her (mock?) enigmatically: "Are you sure?" One can read the paradoxical inference (she hallucinated reading the article) but as it;s also just tossed off by the dubbing so if that meaning was there it's become lost in translation, but it's also typical of the gaslighting tactics husbands and their young lovers (or daughters and gigoloo acid dealing boyfriends) employ to destabilize a saintly momma in Italy's many soapy romantic thrillers. Especially in the age of the"Valley of the Dolls" era-- (the 60s-70s) wives could no longer always tell what reality was thanks to some blue pill a man who says he's her doctor keeps giving her--is he arranging gaslight-style scenes to make her think she's hallucinating? Put strong acid in her Valiums and play weird tape recordings of dead husband's voice under her bed (as they do in The Big Cube) and you can get her to jump off the roof into the sea while you're safely miles away with perfect alibis. It lets the filmmaker use all sorts of crazy images and unresolved ellipses (way better than the "it was all a dream" defense.

Again all these little tangents go nowhere, they're really more misdirection and paranoia-boosters, both aspects helping to make the ensuing murders that much more traumatizing - especially as they're so blunt an inexorably straightforward, like a raw unedited nightmare. After the incident in the kitchen with the staring and blood mopping, both parents are out and Anna is alone in the house with Bob, who's playing with his remote control car in the living room, the setting for another of the film's inexorable but natural progressions from one small thing to another until the trap swing shut. First Bob's the car turns a corner toward the kitchen out of his sight; Bob turns the corner wondering why it hasn't driven back; it's gone and there's no sound of it revving; the basement door, which is usually locked, is wide open however. Bob goes down into the gloom to look for it and disappears from view. A moment later Anna comes into frame and calls to him; he doesn't answer. She looks down the basement steps, and slowly goes down into the basement to look for him. Suddenly the door slams shut above and locks her in and some shadowy thing comes moving towards her from the far end of the basement. She's fucked. She starts screaming for Bob but he's somehow upstairs. It's so a simple logical progression: the remote control car disappearance leading to the babysitter locked in a cellar. She's screaming for Bob to open the door as Freudstein starts shambling towards her out of the gloom. But Bob isn't going to open the door unarmed, so he's collecting his stuffed monkey and flashlight while she's screaming and pounding at the door and the killer's lurching slowly towards her...

![]()

The glacial pace in which Bob suits up to walk across the kitchen floor -taking his sweet time -as she's cut to ribbons on the other side of the door is maddening, that borrow of Leopard Man thrown into an infinite loops, and yet we certainly can't fault Fulci for choosing 'nightmare time' frame for the action, the slowing down rather than speeding up is just what real nightmares are like. There's no time or space in a nightmare-- no logic rhyme or reason -running three steps can take an hour and a ten miles crossed in a single second. Here it's the former and a sense of fatalism overtakes us as, one after another, the adults trundle down into the basement to their deaths. We already know no one can be spared--from the tapes of the previous tenant/researcher that Dr. Boyle listens to: "Oh my god, not the children! "The blood! Blood! Not only blood.... his voice!" That terror in the tape is the most emotional of all the voices in the film. It settles over the rest of the film like a pall.

Demerits for some terrible dubbing, especially the lady playing Bob like he's always counseling a simpleton in a terrible 60s movie (which is why I can use that word) but that sense of wrongness helps to give it all a nightmare fatalism. The dad's declaration after dragging the family away from comfy upscale NYC, a dismissal of their needs and concerns, "You're gonna love it, smell that country air," is also strangely unconvincing --carrying no authority and raises suspicions he's woefully inadequate as a father. You could be coming to him bleeding and on fire and he'd wave it away as new school jitters. It can drive viewers insane but that's part of why it works as a nightmare logic parable -simple buildups from normal tiny incidents seeming slightly out of joint --the way no one in the family really hear what one another is saying - which is why Anna's ominous silence carries such a charge and says way more than all the generic small talk of the mother. If it gets too frustrating to see a whole family helpless to escape a limping armless dead man who can barely shamble, preferring to cower and die helpless and screaming when it would be a simple thing to chop off his other arm (or at least use your own) well, that's how nightmares are and who knows how we'd really act and maybe that's where the horror is -- the realization that if the shit got heavy enough we'd crumble into a sweaty sobbing ball. At least in this case we can imagine the terror really is overwhelming - that this thing has been living below them all the while and has been for over 70 years, repairing itself through limb replacement until all that's left is walking death - this is the first time they see it, and the last--as if the full horror of Freudstein's shambling maggoty cadaver is so overwhelming it paralyzes the prey, jams the record so it hops a groove and leaves you screaming on an eternal skip--a kind of instant repression black-out.

That's why the film's chamber piece momentum works so well, almost like a three act opera, as all the paranoid 'almost' sub-plots evaporate in the cold finality of the basement, the illogic that a row of corpses could be strung up down there without the smell carrying upstairs through the same crack in which Bob crawls for his own escape (trying to fit his head through that narrow crack provides one last nerve shredding moment that stretches forever) into Mae's and Mother Freudstein's sympathetic decades-departed arms--is so startling, original and final. There is no death but what we make for ourselves, which is called waking up, the alarm clock of your tender throat raw from claw-choked screaming, pulled up from the pillowy grave like sluggish screaming Lazarus Jr. by a girl who died before your grandmother was born, to a world with its own set of rules, but the same damned house. Or to put in layman's terms, it's the end of The Shining if its Danny who wound up at the party in 1929, or at least upstairs with a babysitter and those cool creepy twins... forever... and ever...And mind your manners--you know some other guest is sure to drop in.

NOTES

1.(since it's going to be dubbed and subtitled in about 20 different languages, Italian film tradition is to shoot MOS (without sound) or silently - each actor in the international cast speaking his or her own language and then dubbing their part for that country's track, ideally, and voice actors in that language doing the rest, which is why nearly every character in Italian horror sounds like one of two or three different voice actors. No one knows their names or where they are - the invisible heroes of the business- as a voiceover actor myself I say their stories must be told!

Again all these little tangents go nowhere, they're really more misdirection and paranoia-boosters, both aspects helping to make the ensuing murders that much more traumatizing - especially as they're so blunt an inexorably straightforward, like a raw unedited nightmare. After the incident in the kitchen with the staring and blood mopping, both parents are out and Anna is alone in the house with Bob, who's playing with his remote control car in the living room, the setting for another of the film's inexorable but natural progressions from one small thing to another until the trap swing shut. First Bob's the car turns a corner toward the kitchen out of his sight; Bob turns the corner wondering why it hasn't driven back; it's gone and there's no sound of it revving; the basement door, which is usually locked, is wide open however. Bob goes down into the gloom to look for it and disappears from view. A moment later Anna comes into frame and calls to him; he doesn't answer. She looks down the basement steps, and slowly goes down into the basement to look for him. Suddenly the door slams shut above and locks her in and some shadowy thing comes moving towards her from the far end of the basement. She's fucked. She starts screaming for Bob but he's somehow upstairs. It's so a simple logical progression: the remote control car disappearance leading to the babysitter locked in a cellar. She's screaming for Bob to open the door as Freudstein starts shambling towards her out of the gloom. But Bob isn't going to open the door unarmed, so he's collecting his stuffed monkey and flashlight while she's screaming and pounding at the door and the killer's lurching slowly towards her...

The glacial pace in which Bob suits up to walk across the kitchen floor -taking his sweet time -as she's cut to ribbons on the other side of the door is maddening, that borrow of Leopard Man thrown into an infinite loops, and yet we certainly can't fault Fulci for choosing 'nightmare time' frame for the action, the slowing down rather than speeding up is just what real nightmares are like. There's no time or space in a nightmare-- no logic rhyme or reason -running three steps can take an hour and a ten miles crossed in a single second. Here it's the former and a sense of fatalism overtakes us as, one after another, the adults trundle down into the basement to their deaths. We already know no one can be spared--from the tapes of the previous tenant/researcher that Dr. Boyle listens to: "Oh my god, not the children! "The blood! Blood! Not only blood.... his voice!" That terror in the tape is the most emotional of all the voices in the film. It settles over the rest of the film like a pall.

Demerits for some terrible dubbing, especially the lady playing Bob like he's always counseling a simpleton in a terrible 60s movie (which is why I can use that word) but that sense of wrongness helps to give it all a nightmare fatalism. The dad's declaration after dragging the family away from comfy upscale NYC, a dismissal of their needs and concerns, "You're gonna love it, smell that country air," is also strangely unconvincing --carrying no authority and raises suspicions he's woefully inadequate as a father. You could be coming to him bleeding and on fire and he'd wave it away as new school jitters. It can drive viewers insane but that's part of why it works as a nightmare logic parable -simple buildups from normal tiny incidents seeming slightly out of joint --the way no one in the family really hear what one another is saying - which is why Anna's ominous silence carries such a charge and says way more than all the generic small talk of the mother. If it gets too frustrating to see a whole family helpless to escape a limping armless dead man who can barely shamble, preferring to cower and die helpless and screaming when it would be a simple thing to chop off his other arm (or at least use your own) well, that's how nightmares are and who knows how we'd really act and maybe that's where the horror is -- the realization that if the shit got heavy enough we'd crumble into a sweaty sobbing ball. At least in this case we can imagine the terror really is overwhelming - that this thing has been living below them all the while and has been for over 70 years, repairing itself through limb replacement until all that's left is walking death - this is the first time they see it, and the last--as if the full horror of Freudstein's shambling maggoty cadaver is so overwhelming it paralyzes the prey, jams the record so it hops a groove and leaves you screaming on an eternal skip--a kind of instant repression black-out.

NOTES

1.(since it's going to be dubbed and subtitled in about 20 different languages, Italian film tradition is to shoot MOS (without sound) or silently - each actor in the international cast speaking his or her own language and then dubbing their part for that country's track, ideally, and voice actors in that language doing the rest, which is why nearly every character in Italian horror sounds like one of two or three different voice actors. No one knows their names or where they are - the invisible heroes of the business- as a voiceover actor myself I say their stories must be told!